On July 5, finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman presented her maiden Union Budget 2019 in the parliament with a roadmap to turn India into a $5 trillion economy by 2025. During her presentation, she referred to zero budget farming, which, she claimed, can double the Indian farmers’ income.

More than 1,500 kilometres away, in Sonwati village in Latur, which falls under drought-hit Marathwada region of Maharashtra, Sandipan Badgire is least concerned about the $5 trillion economy. While Sitharaman “set the ball rolling for a New India“, Badgire, a farmer, kept staring at his dry farmland, occasionally looking up towards the sky and praying for it to rain.

“We are into the second week of July and there is no monsoon rainfall in Latur. No sowing of kharif [monsoon] crops has taken place because we depend on rains for farming,” said Badgire. “Under normal monsoon conditions, we sow kharif crops by mid-June. This year, we are already delayed by three weeks and it seems rains won’t come till mid July. Thus, a delay of a month in sowing, which will lead to crop productivity loss of 30-40 per cent,” he lamented.

Zero budget farming is a joke on drought-hit farmers, claim farm activists in Maharashtra. Credit: Nidhi Jamwal

Zero budget farming is a joke on drought-hit farmers, claim farm activists in Maharashtra. Credit: Nidhi Jamwal

Another 130 kms away, situation is no different in Parbhani district of Marathwada. “Of the total 550,000 hectare area in the district, which is covered under kharif sowing, this year barely 125,000 hectare has been sowed with kharif crops,” informed Vilas Babar, a farmer and a member of the Communist Party of India (Marxist) in Parbhani.

“In the last week of June, some blocks of Parbhani received scattered rainfall and farmers went in for sowing. But thereafter, we have had no rains and fear the sowing will be lost leading to financial losses to the farmers, who are already burdened by sultani [caused by the government] and aasmani [caused by lack of rains] drought,” said Babar.

“Farmers in Maharashtra are facing successive droughts. Rather than understanding their plight and supporting them, the finance minister is telling farmers to go back to basics and adopt zero budget farming to double their income. This is a joke on the farmers,” said Vijay Jawandhia, a senior farm leader from Vidarbha region. “If the government is so confident that zero budget farming can double the farmers’ income, why does it not shut down all chemical fertiliser and pesticide factories in the country?” he questioned.

Meanwhile, agriculture experts are also raining concern over delayed monsoon and sowing in the country. “Delayed sowing decreases the duration of grain filling in rice and wheat, which leads to reduced grain size and eventually low crop yield,” said Om Prakash Ghimire, crop physiology expert with Fasal, a Bengaluru-based artificial intelligence startup working with the farmers.

But, timely sowing of kharif crops depends on the monsoon rainfall. According to NITI Aayog, over 52 per cent agriculture land in the country depends on rainfall for irrigation. Of the total pulses, oilseeds and cotton produced in India, 80 per cent pulses, 73 per cent oilseeds and 68 per cent cotton come from rain-fed agriculture.

Delayed sowing will lead to 30-40% crop productivity decline in Marathwada, says Sandipan Badgire, a farmer from Sonwati village in Latur. Credit: Nidhi Jamwal

Delayed sowing will lead to 30-40% crop productivity decline in Marathwada, says Sandipan Badgire, a farmer from Sonwati village in Latur. Credit: Nidhi Jamwal

But, this year the onset of monsoon in the country was delayed. As against a normal onset date of June 1, the southwest monsoon hit Kerala coast on June 8. The financial capital of the country, Mumbai, where monsoon normally arrives on June 10, faced a delay of more than two weeks as monsoon arrived only on June 25.

As of July 7, which is five weeks into the southwest monsoon season (June to September), the all India rainfall departure is minus 21 per cent.

“This much all India rainfall deficiency was not expected. We expected a delay in monsoon by about six to 10 days in the country. Also, Cyclone Vayu slowed down the monsoon progress,” M Rajeevan, secretary, Union ministry of earth sciences told Gaon Connection. “Only in the last 10-15 days the monsoon is progressing. We have good hope the monsoon will strengthen and revive. As per our extended range forecast, we are expecting surplus rainfall during the second half of July, which should ease out the present deficiencies,” he added.

All India decline in kharif sowing

The delayed onset of monsoon in the country is showing its impacts. As of July 5, about 52.47 lakh hectare area is covered under rice across the country. Last year (corresponding week), this figure stood at 79.36 lakh hectare. Thus, a reduction of about 34 per cent in rice plantation, as noted in the all India kharif crop situation data of the Department of agriculture cooperation and farmers welfare.

Similar decrease in kharif sowing has been recorded in case of pulses, coarse grains and oilseeds. As against 27.51 lakh hectare area under pulses last year , this year only 7.94 lakh hectare is covered — a reduction of 71 per cent.

Last year 51.06 lakh hectare was under coarse cereals, which stands at 37.27 lakh hectare till July 5 this year — a reduction of 27 per cent. Oilseeds have been planted in 34.02 lakh hectare area as against 62.68 lakh hectare last year — a reduction of about 46 per cent.

As of July 5, there is an all India decline of 34% in kharif rice area, 71% decline in pulses area, and 46% decline in oilseeds area across the country, as compared to last year (corresponding week)

As of July 5, there is an all India decline of 34% in kharif rice area, 71% decline in pulses area, and 46% decline in oilseeds area across the country, as compared to last year (corresponding week)

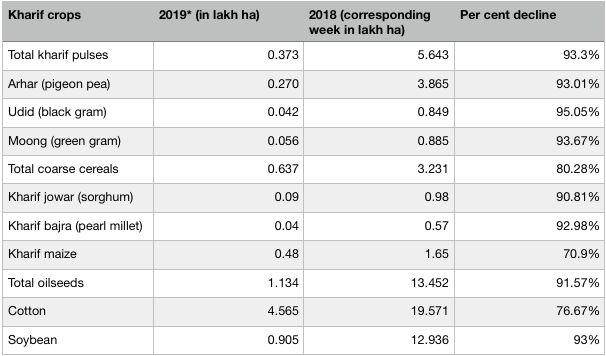

Over 93% decline in sowing of kharif pulses in Maharashtra

Kharif area decline has been registered in Maharashtra as well, whose Marathwada and Vidarbha regions are facing deficient monsoon rainfall.

As of July 7, Marathwada has a rainfall departure of minus 34 per cent, which is categorised as ‘deficient’ rainfall by the India Meteorological Department (IMD). Districts such as Hingoli, Nanded, Parbhani, Latur in Marathwada have rainfall departure of minus 60 per cent, minus 51 per cent, minus 39 per cent, minus 32 per cent, respectively.

Vidarbha region, too, has a rainfall departure of minus 20 per cent. Districts such as Yavatmal, Washim, Amravati have rainfall departure of minus 47 per cent, minus 36 per cent, minus 27 per cent, respectively.

Predictably, there is a decline in kharif sowing in the state, as reflected in the data of the Department of agriculture cooperation and farmers welfare (see table: Decline in kharif sowing in Maharastra 2019-20).

Interestingly, in spite of an acute drought in the state, there has been negligible decline in area under sugarcane, a water guzzling crop. The normal average sugarcane area (average from 2013-14 to 2017-18) in the state is 8.98 lakh hectares. As of July 3, area sown under sugarcane remains 8.40 lakh hectare.

Table: Decline in kharif sowing in Maharastra 2019-20 (in lakh hectare area)

Note: * as of July 3, 2019

Source: Department of agriculture cooperation and farmers welfare, Ministry of Agriculture & Farmers Welfare, Government of India.

Successive back-breaking droughts

Farmers in Maharashtra are facing successive droughts. Last October, the state chief minister, Devendra Fadnavis, declared almost half the state as drought-hit.

“In the last five years, three years have been drought years — 2014-15, 2015-16 and 2018-19. With every passing year, drought keeps getting worse. How long can farmers withstand it?” questioned Babar.

He alleged the government had failed to support the farmers. “About two-and-a-half years back, the Centre released an updated drought manual introducing strict parameters to declare drought. Because of this new manual, several drought-struck villages in Purna and Jintur talukas of Parbhani have not been included in the official list of drought-hit villages,” said Babar.

According to Badgire, this year’s drought is worse than all the previous drought years. “Last monsoon season, we had kharif crop loss of 50 per cent due to erratic and deficient rainfall. Thereafter none of the farmers took any rabi [winter] crop. In spite of such extreme situations, both the government and the media failed to make drought an election issue in the recent Lok Sabha elections,” he complained.

Farmers in Marathwada are dependent on private water tankers and private RO water plants. Credit: Nidhi Jamwal

Farmers in Marathwada are dependent on private water tankers and private RO water plants. Credit: Nidhi Jamwal

Farmers in Sonwati village of Latur are completely dependent on private water tankers. “Buying 500 litres water from a water tanker costs Rs 150, which sustains for about three days. We are also buying RO drinking water from private companies that have set up RO plants in almost all villages of Marathwada,” added Badgire. The RO water is sold at a rate of Rs 15-20 per 20 litre water can. “RO companies are mindlessly drawing groundwater, purifying it and selling to villagers to make a killing,” he added.

Farm activists allege other ‘pro-farmer’ schemes have also failed to make a dent in the growing farm crisis in the country.

“There are technical problems with the recently announced PM-Kisan scheme, which has promised Rs 6,000 per year to each farmer in the country,” said Maruti Kurwatkar of Rajura tehsil in Chandrapur. For instance, if the 7/12 (land record) is in the name of four brothers, it is not clear in the scheme if one brother will receive Rs 6,000, or all four will receive the promised amount. “So right now, the district administrations are collecting Aadhar card and 7/12 of farmers under PM-Kisan scheme, but not releasing any money, as it is awaiting policy clarification from the Centre,” said Kurwatkar.

On being contacted, a member of Parbhani zilla parishad told Gaon Connection that none of the farmers had received any money under the PM-Kisan scheme. “We have written applications to the collector to release the money, but no progress so far,” he said.

‘Zero budget farming a joke on drought-hit farmers’

Farmers allege that in the present scenario of successive droughts, declining crop yields and growing farmer suicides, finance minister Sitharaman’s call for farmers’ to go back to zero budget farming was a joke.

Farmers have brought their cattle to cattle camps to tide over the drought. Credit: Nidhi Jamwal

Farmers have brought their cattle to cattle camps to tide over the drought. Credit: Nidhi Jamwal

“The government does not want to address the real issues being faced by the farmers. Instead, it has conveniently pushed the entire onus on the farmers to double their income by adopting zero budget farming,” lashed out Jawandhia. “Why did the finance minister not declare doubling the wages of farm labourers under the MGNREGA and make a provision for the same in the budget?” he asked.

Simply put, zero budget farming is a form of natural farming that does not use chemical fertilisers and pesticides, and the ‘input’ cost of farmers in zero. Subhash Palekar of Vidarbha has been promoting zero budget farming and was awarded Padma Shri for the same in 2016.

“Zero budget farming is a joke on drought-hit farmers. The concept sounds good, but farmers need to pay to buy seeds and manure, look after their cattle, pay farm labourers, etc,” said Babar. Even if we save our own seeds and make our own manure, it costs to rear cattle. Where is the fodder? Where is the water? Banks don’t give us loan, so we take loan from private money lenders at an interest rate of 5-10 per cent per month, said Babar.

Kurwatkar said zero budget farming was not practical in today’s world when farmers have to feed millions of mouths and climate change is increasing the risks in agriculture.

Incidentally, during the recent Gaon Connection Survey conducted across 19 states, every fifth farmer interviewed said climate change was a big challenge in farming. In Maharashtra, every second farmer raised concern around climate change.

To help farmers cope with the changing climate, the IMD is setting up additional 550 field units with the help of Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR) at their Krishi Vigyan Kendras. “We have started block level forecasts with 200 blocks, which will be increased to 6,600 blocks by next year,” said Rajeevan.

But, in climate change three things are very sure: “Heavy rainfall events are increasing and will further increase in future. Heatwave frequency, duration and intensity are increasing and will further increase in future. Duration of dry periods during monsoon season will increase further with reduced number of rainy days. When it rains, it will rain heavily. Farmers should adopt strategy accordingly,” added Rajeevan.

Farmers are demanding only two things to make agriculture profitable — timely rainfall, and a higher minimum support price (MSP) that takes into consideration the real input costs of farming. The Centre has recently increased the minimum support price (MSP) of some kharif crops, such as paddy, jowar, ragi and pulses.

“Raising the MSP by Rs 80 or Rs 100-200 per quintal will not alleviate farmers’ condition, as the government has also raised per bag cost of fertiliser by Rs 200. Price of diesel and petrol has also been increased,” said Jawandhia.