Shahjahanpur/ Varanasi/ Barabanki, Uttar Pradesh

Renu Devi works at an anganwadi kendra, a government-run early care centre, in Shahjahanpur district, Uttar Pradesh. Her day is filled with the sight and sound of kids wailing — for food.

“They are hungry, but what do we feed them,” she asked as she tried to pacify them. “The children were happy when they were provided a freshly cooked meal at the anganwadi. But that stopped with the pandemic and we only get dry rations now,” Renu Devi, who works in Bhawal Kheda village, told Gaon Connection.

According to her, the children were in her care at the anganwadi daily for four hours.

“It is difficult to look after hungry kids. Their share of dry rations are handed over to their guardians when they come to pick the children up,” she added. The dry ration kit generally includes daal (pulses), chawal (rice), chana (grams), and daliya (broken wheat or lapsi) mixture.

The anganwadi centre at Bhawak Kheda village is one of 189,309 such centres in Uttar Pradesh that have not resumed hot cooked meals for more than two years now.

Also Read: If children could vote: In poll-bound UP, high malnourishment but 66% POSHAN funds unutilised

At the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020, anganwadis across the country were shut down and all the state governments started supplying dry rations to the beneficiaries under the Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) scheme of the Government of India.

ICDS is the world’s largest programme for early childhood care and development, with over 158 million children (2011 Census) in the 0-6 years age group, and pregnant and lactating mothers in the country. It offers six services: supplementary nutrition, preschool non-formal education, nutrition and health education, immunisation, health check-up and referral services, through 1.36 million functional anganwadi centres spread across all the districts in the country (as of June 2018).

Post pandemic, most state governments have resumed hot cooked meals at their anganwadi centres, with some having added more nutritious food items in their daily menus (such as millets) to make up for the loss of calories and rising malnutrition in the wake of the COVID-19.

But, Uttar Pradesh has continued with the dry ration supplies even though the anganwadis have opened and children, between the age groups of three and six years, daily (Monday to Saturday) visit these centres for early education and healthcare.

Anganwadi workers and helpers complain that they find it difficult to manage young children without serving them cooked food at the centre.

It has been tough, said Zainab Begum who works at the Kazipur anganwadi centre in Shahjahanpur. “The children who come to our centre are very young. Ideally, we should be giving them a banana or some other fresh fruit and nutritious food,” she told Gaon Connection. But, there is no such food at the centre to feed the children. When they cry for food, we send them back home, she lamented.

In September this year, Gaon Connection visited several anganwadi centres in Varanasi, Barabanki, and Shahjahanpur districts. The workers and helpers complained that the food was in short supply. Some anganwadi centres lacked basic infrastructure, such as a pucca room, or a ceiling fan, or a toilet.

In Varanasi district, which is also Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s constituency, there are 3,914 anganwadis centres. In the Kashi Vidyapeeth block, there are 574 such centres. Some of them are well maintained, but some are in a sorry state.

For instance, an anganwadi centre at Malin Basti near the Manduadih railway station functioned under a tree. “We declare a holiday whenever it is too hot or it rains too much,” Maya Rai, an anganwadi worker at the centre, told Gaon Connection.

“We have to bring the supplies that we need everyday and take them back with us as there is nowhere we can keep them,” she said. This anganwadi has 33 children between the ages of three and six years. “Because it is run outdoors under a tree, many parents do not want to send their children here. Often my colleagues and I go to each home and bring the children here,” she added.

Malnutrition: The silent pandemic

Globally, an estimated 149 million children are stunted (chronically undernourished) and 50 million are acutely undernourished (wasted), with undernutrition a direct or underlying cause in 45 per cent of all child deaths.

COVID-19 pandemic has compounded these problems as food supplies have been affected and immunisation has taken a hit too. According to The Lancet, “the COVID-19 pandemic is undermining nutrition across the world, particularly in low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs). The worst consequences are borne by young children.”

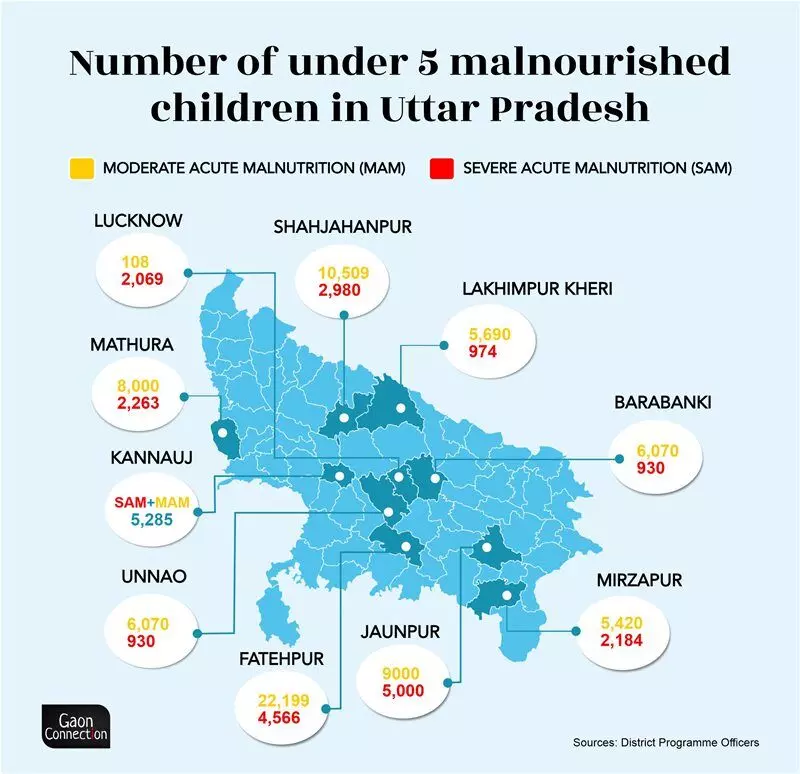

In July 2021, while replying to a question, Union Minister for Women and Child Development Smriti Irani informed the lower house of the Parliament that there are a total of 927,606 children that are identified as severely acute malnourished (SAM).

She went on to inform the house that amongst these, 398,359 children are from Uttar Pradesh.

Further, as per the National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5) of 2019-21, in rural Uttar Pradesh, 41.3 per cent of under-5 kids were stunted (low height for age), while 33.1 per cent under-5 kids were underweight (low weight for age). Seventeen per cent rural under-5 kids in the state were categorised as wasted (weight for height), and 7.1 per cent were severely wasted.

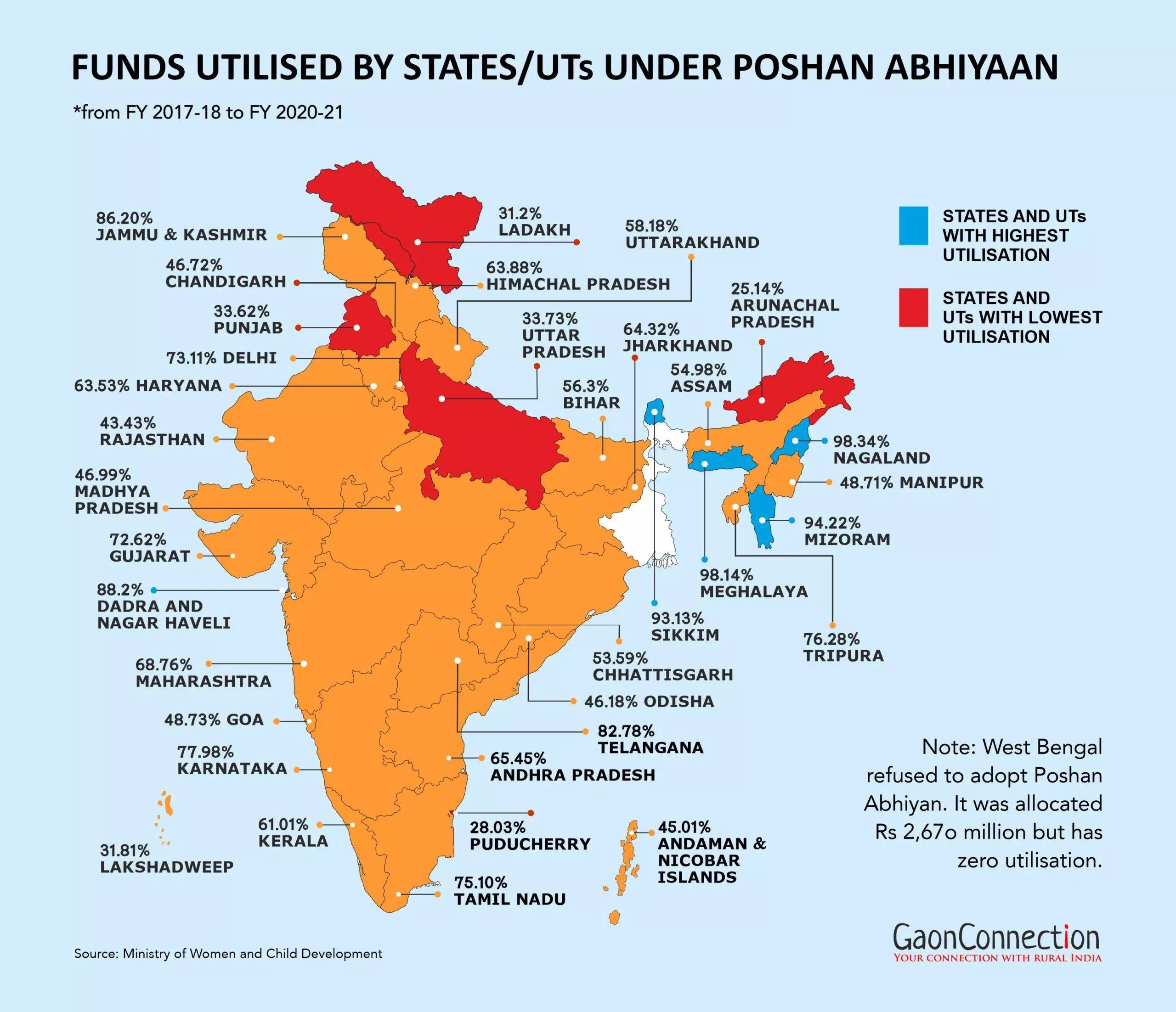

Despite high malnutrition in the state, Uttar Pradesh is one of the worst performers in utilising funds allocated for the POSHAN (Prime Minister’s Overarching Scheme for Holistic Nutrition) mission. The state failed to utilise 66.27 per cent of its funds (from 2017-18 to 2020-21, see map).

And, it has not restarted hot meals at the anganwadi centres. Beneficiaries — under-six children, and pregnant and lactating mothers — are being distributed dry rations.

Also Read: If children could vote: In poll-bound UP, high malnourishment but 66% POSHAN funds unutilised

Dry rations don’t quite cut it

Distributing dry rations (uncooked dal, rice, chana and dailya) instead of cooked meals make it difficult to guarantee that the food would actually be consumed by the children, anganwadi workers pointed out.

“The entire family partakes of it and the children do not get their required number of calories and nutrition,” Marushi, a worker at Varanasi’s Adarsh Bal Vidyalaya, said. “I don’t think the dry rations they get now are enough to keep malnutrition away,” she added.

“We do get the dry rations, but the daliya they give is usually used to feed animals,” Jameen Anwar, whose son comes to the anganwadi centre at Adarsh Bal Vidyalaya, told Gaon Connection.

Take home ration for anganwadi children. Photo: Abhishek Verma

“The anganwadi would have cooked the nutritious daliya in the proper way. Now we just send some lunch with our son when he leaves for the anganwadi,”Anwar said.

According to him, there was a time [before pandemic] when even ghee was supplied , but not anymore. “The government must do something to improve matters,” he said.

Also Read: 8 out of 10 Indian households faced food insecurity last year despite free ration relief: Survey

“We provide daal, daliya, oil and rice in the dry rations for the children. We ensure this protects them from malnutrition,” Yugal Kishore Sanguri, the district programme officer for the ICDS in Shahjahanpur, told Gaon Connection.

DK Singh, the district programme officer, Varanasi, informed that there were 45,000 malnourished children, and 4,500 severely malnourished children in the district. And, the district authorities were trying to bring down that number.

“As September was national nutrition month in the district, several programmes were underway to spread awareness about malnutrition,” Singh said. The district official also made an assurance that the authorities would look into the matter of the open air anganwadi centre in Malin Basti and set it right.

Also Read: UP govt hikes honorarium for anganwadi workers, but they call it an eyewash

Many states resumed serving fresh meals

While Uttar Pradesh is yet to resume hot meals at its anganwadi centres, several states such as Madhya Pradesh, Jharkhand, Odisha, and Tamil Nadu, have resumed serving hot cooked meals to the children.

Take home ration for anganwadi children. Photo: Abhishek Verma

At Pipardhaba anganwadi in Kini village in Chainpur block of Jharkhand’s Palamu district, Sandhya Devi, a 40-year-old, anganwadi teacher stated that cooked meals were resumed at the centre from December 15, 2021.

“We give them halwa [pudding], chana-gud [jaggery-gram] in the morning, and rice, daal and sabzi [vegetables] in the afternoon,” Devi told Gaon Connection.

Similarly, in Madhya Pradesh, Archana Ahirwar, an angwanwadi worker at Ahmadpur village in Vidisha district said that cooked meals are provided to the children as per the diet chart. “In the morning, the children eat namkeen daliya or khichdi. In the afternoon, they have poori sabzi, kheer, daal-chawal, lapsi, and sattu,” Ahirwar told Gaon Connection.

SRS Subramanian, a member of the Coimbatore-based The International Centre for Child and Public Health, said that cooked meals at the government schools and the anganwadi centres were resumed in Tamil Nadu ever since the lifting of the lockdown.

“Fresh meals are cooked with rice, dal, oil, salt, bengal gram, green gram, and eggs,” Subramanian told Gaon Connection.

“In Odisha, children at the anganwadi centres are provided eggs five days a week. The breakfast also includes sprouts and chikki [peanuts and jaggery sweetmeal]. In some districts, the children are also being provided with ragi laddoo. Once a week, they are provided with daalma [rice cooked with vegetables],” Sameet Panda, a Bhubaneswar-based food activist working for the nationwide Right To Food campaign, said.

“The rationale behind suspending these meals at the centres during the pandemic was to promote physical distancing. But that should not become an excuse for the state governments not to provide nutritious food to the children who are the future of this country,” Panda told Gaon Connection. “It is the state’s responsibility to ensure nutrition to children from underprivileged sections of the society,” he said.

“Education and nutrition have to go hand in hand. It’s a beautiful idea and should be implemented well. There’s no way you can make a hungry child study!” Panda added.

“It has long been recognized that poor childhood nutrition and associated social and environmental factors, including poverty, crowding, maternal depression, low maternal IQ, and child maltreatment, strongly affect cognitive, language, and socio-emotional development,” a study titled Neurodevelopmental effects of childhood malnutrition: A neuroimaging perspective, published in the ScienceDirect journal on May 1, 2021, noted.

Satish Gadi, a Gurugram-based senior physician, who has been a doctor in the Indian Army and was posted as Chief Medical Director at the Indian Railways before retiring, remarked that child malnutrition ultimately leads to a vicious cycle of negative outcomes in life.

“We have so much investment in health but we fail to deliver where it’s most needed — ensuring proper nutrition to a child for at least the first six years of life. No matter how you intervene in public health, if the coming generations are of those who have been stunted, wasted, underweight or malnourished during the childhood stage, not much can be achieved,” he told Gaon Connection.

UP to resume hot meals soon

When Gaon Connection approached Sarneet Kaur Broca, the director of the Bal Vikas Seva Evam Pushtahar Vibhag [ICDS] in Uttar Pradesh, he informed the hot cooked meals at anganwadis were about to begin from next month in January.

“Uttar Pradesh will resume its hot cooked meals programme in January. The exact date will be announced soon,” Broca told Gaon Connection.

Previously, while reporting on the unutilised funds to eradicate child malnutrition in the state, the erstwhile director Sarika Mohan had informed that the plans were underway to merge the mid-day meal scheme with the anganwadi scheme with the collaboration of the two departments of education with the ICDS.

Broca, however clarified that the collaboration would not be on the departmental level but at the ground level.

“Basically, the idea is to cook food for children in a single project. The food for the anganwadi and the mid-day meal will be cooked together in a single choolha [kitchen] at the schools for the sake of convenience and economic efficiency,” Broca told Gaon Connection.

Meanwhile, kids at anganwadi centres in Uttar Pradesh await the resumption of cooked meals.

Written by Pratyaksh Srivastava. With inputs from Ramji Mishra in Shahjahanpur (Uttar Pradesh), Virendra Singh in Barabanki (UP), Ankit Singh in Varanasi (UP), Pankaja Srinivasan in Coimbatore (Tamil Nadu), Ashiwni K Shukla in Palamu (Jharkhand).