Mirtala (Mahoba), Uttar Pradesh

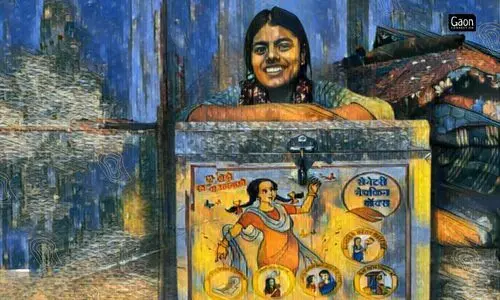

In a room, with green painted walls, and a sagging clothesline, stood a shiny tin baksa (box) in a corner, locked. The keys to it were with 22-year-old Kalpana. “Should I unlock it,” she asked, and sat on the floor to do so. The box had packets of sanitary pads, bars of Dettol soaps, some booklets, and a register.

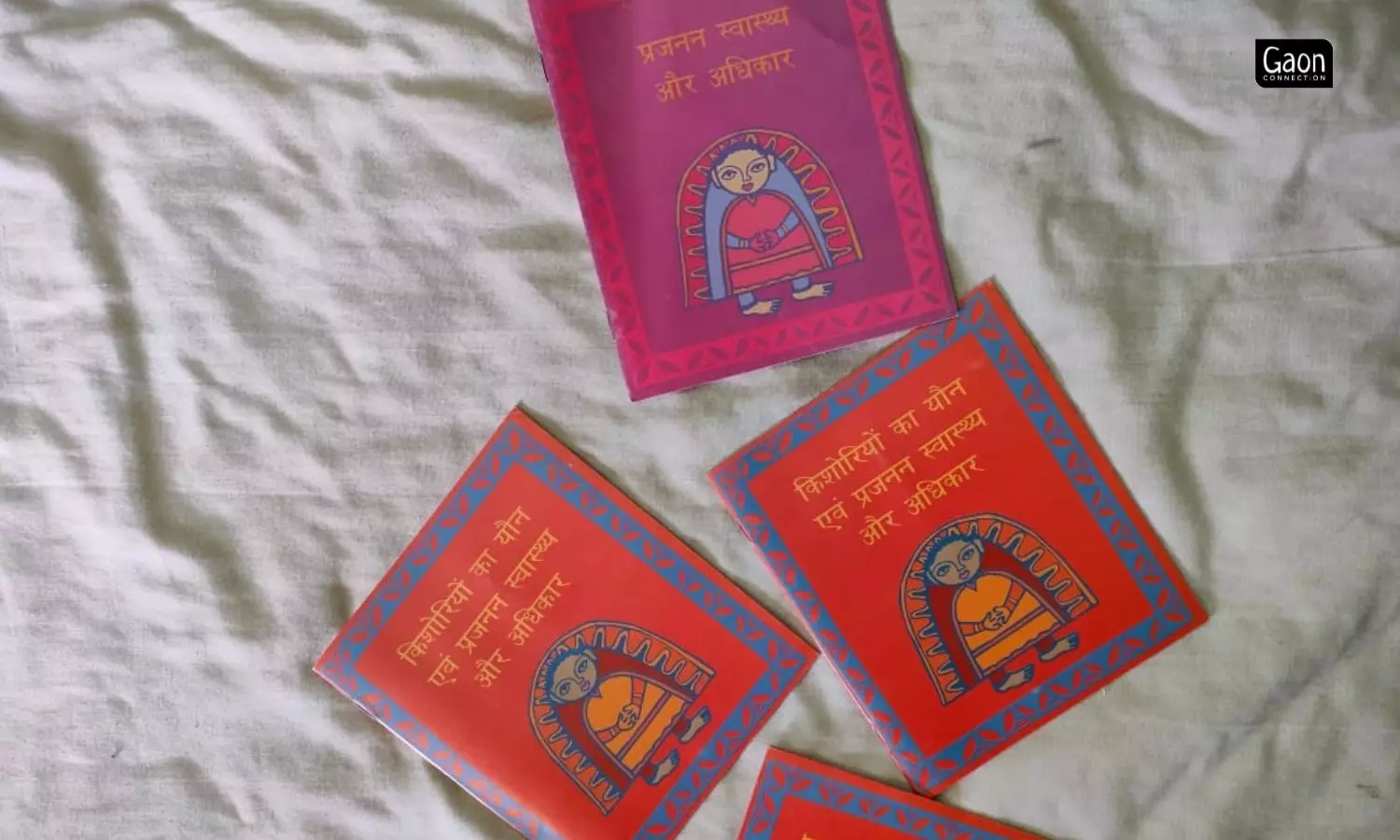

The red and magenta booklets were awareness materials, which have information about puberty-related changes, periods, and sexual care. The register is to maintain the names of the girls who run to Kalpana didi as soon as a need for sanitary pads arises.

The red and magenta booklets were awareness materials, which have information about puberty-related changes, periods, and sexual care.

Kalpana, a resident of Mirtala village in Mahoba, Uttar Pradesh, charges Rs 20 per packet of six pads, and throws in a dettol soap for free, if someone buys two packets. The young lady runs a ‘sanitary pad depot’ from this room in her house.

Also Read: MeraPad sanitary napkins offer eco friendly and hygienic alternative to rural women

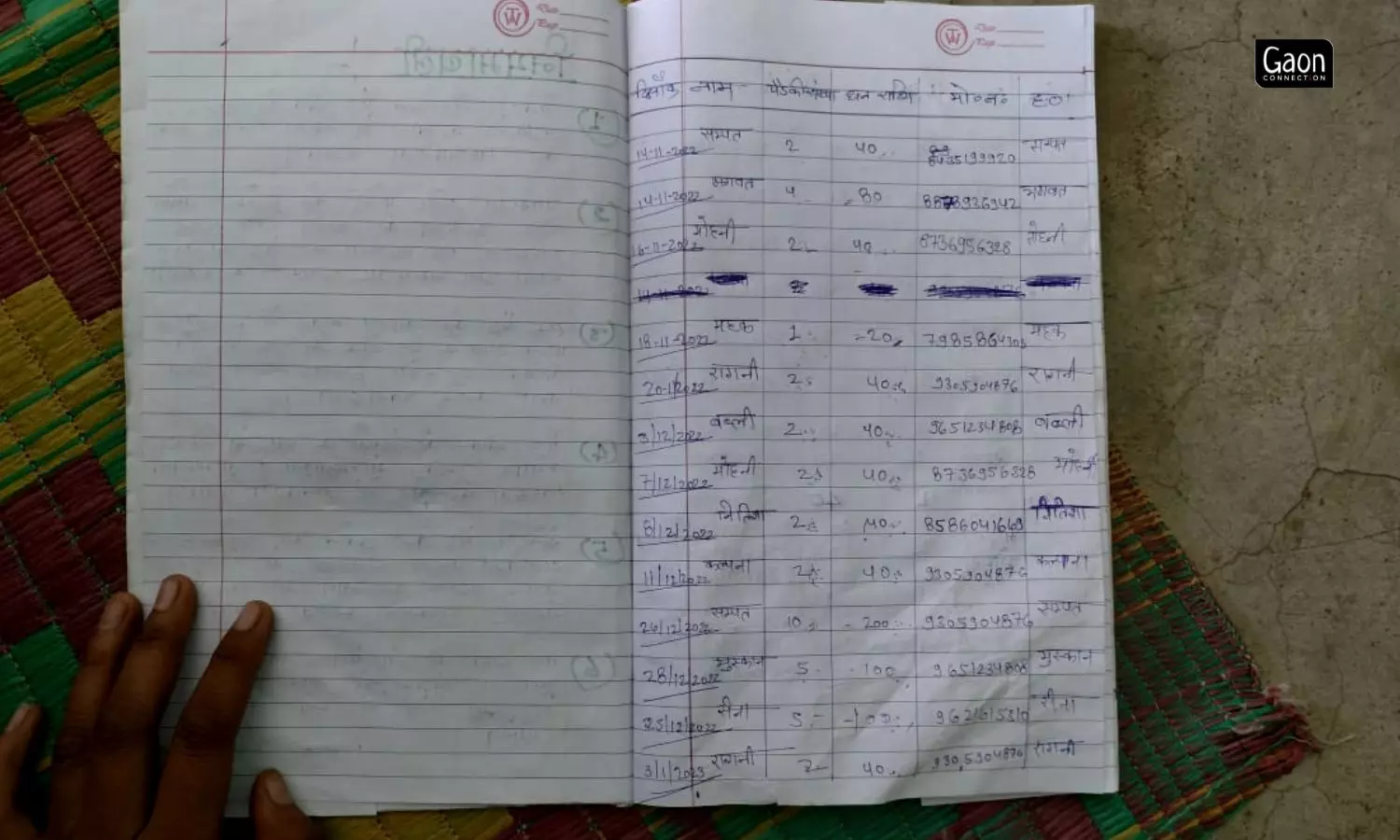

The register has been maintained since November 2022, and Kalpana said she had already given out 69 packets of sanitary towels, till mid-April this year. Mahoba-based non-governmental organisation Gramonnati has trained and supported her to run the ‘sanitary pad depot’ in her village.

Kalpana is didi for adolescent girls and bitiya for women, who need to discuss their period-related complications, ask questions about their menstruation, or ask for a pad.

Also Read: Adolescents in Rajasthan villages discuss periods and reproductive health, shattering taboos

Narrating an incident, Kalpana said: “Mehek, a village girl, came running to me, crying. She was terrified to find herself bleeding. I unlocked my steel box and gave her a packet of sanitary pads.”

In a room, with green painted walls, and a sagging clothesline, stood a shiny tin baksa (box) in a corner, locked.

“I told her how periods were a normal thing for a growing girl and how all of us get it. I also taught her how to use a pad and how often to change it,” she said.

Mehek could have reached out to her mother, but her instinct to run to Kalpana says a lot about the trust the 22-year-old is weaving with her village community.

The role Kalpana didi is playing in Mirtala village is crucial as menstruation continues to remain a taboo topic in rural India and a large chunk of girls and women still use unhygienic rags and are unaware of menstrual hygiene.

The beginning

The depot was set up during the COVID-19 lockdown in May, 2020 to provide for the menstruation needs of women. During the nationwide lockdown, access to sanitary pads was a challenge which was not part of essential commodities.

Kalpana’s sanitary depot was born out of necessity but it stayed on. The NGO provided her the pads which were available free of cost during lockdown. For girls like Mehek, who live in the hinterlands, it was godsend.

Mehek came running to Kalpana, crying. She was terrified to find herself bleeding. I unlocked my steel box and gave her a packet of sanitary pads.

The NGO has struck a deal with a shopkeeper in Mahoba city, to provide a subsidised rate for the pads when bought in bulk. Kalpana goes to the same shop, 12 kilometres away from her home in Mirtala village, to restock the pad supply.

“I had bought 200 packets. Once, only a handful of them are left, I will go to Mahoba city and buy the pads from the collected money,” Kalpana said.

“The similar quality pads in the village cost us Rs 50 per packet. The shopkeeper charges more here. This turns out to be expensive for the girls here. Moreover, it isn’t easy for them to turn up to ask a male shopkeeper for pads. It is still a big deal here,” the 22-year-old explained.

Discussion on menstruation and menstrual hygiene

Apart from providing sanitary pads, Kalpana also discussed menstrual hygiene with young girls and women in the village. With the capacity building by the NGO, Kalpana has taken over the role of a leader. She holds monthly meetings with village girls, either in the privacy of her house, or in the panchayat bhawan.

The register is to maintain the names of the girls who run to Kalpana didi as soon as a need for sanitary pads arises.

“Whatever we discussed in those meetings, stayed in those meetings. I first started talking about periods, then the use of sanitary pads and graduated on to other intimate hygiene details. We discussed how the girls feel about their changing bodies, how comfortable they are with their puberty, and so on,” Kalpana said.

Women have started to confide in her. “Mohini’s mother came to me the other day, terribly worried about her daughter’s heavy flow. I told her that this could be abnormal and directed her to the district hospital,” Kalpana said. She regularly holds sessions on menstrual hygiene with the village women.

The box had packets of sanitary pads, bars of Dettol soaps, some booklets, and a register.

When Kalpana decided to start a ‘sanitary pad depot’ in her village, the idea was not well-received by her father Munna. “He complained that the village folks taunted him. They said that Munna ki bitiya incites girls and is making them unruly. But my mother always stood by me,” Kalpana said.

She has had her share of period-induced trauma. “I was in ninth standard and had an exam the next day. I saw the blood on my bed. I ran to my mother and said that something was happening and that I was going to die. She told me to use a cloth and go back to sleep,” she recalled.

She remembered how uncomfortable and miserable she was when she went to school, using a wad of cloth as protection. It was both a mental and physical torture she called it. This is one of the reasons the young girl is running a ‘sanitary pad depot’ in her village.

Because Kalpana’s approach is informal, the girls open up to her, not just about menstruation.

“At times it goes beyond that. They discuss their lives and tell me about their aspirations, their hopes and dreams. I am their saheli, they can speak freely to me,” she said.

Also Read: Improving the state of menstrual health during Covid-19