Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh

Not too long ago, Savita, an ASHA bahu in Banthra village, Lucknow district, had to make multiple visits to rural households to convince the inhabitants to consume free medicines for filariasis. And yet, most were reluctant to do so.

But this year has been surprisingly different. Villagers in Uttar Pradesh, the state with the second highest filariasis burden in the country, are coming forward on their own and demanding medicine for the vector-borne disease caused by Culex mosquitoes, which leads to abnormal enlargement of body parts and severe disability.

The ASHAs of Banthra, Lucknow have seen a behavioural change in the village community towards the consumption of anti-filarial drugs.

“Usually, I have had to really convince villagers to take the medicines. They would take the medicine from me but avoided having it right away, saying they would have it later,” the 30-year-old frontline health worker told Gaon Connection.

“But, this time, things are different. Villagers are asking for the medicine and consuming it,” the ASHA bahu said. Banthra village with a population of 5,049 has four ASHAs and one Sangini. It falls under the administration of Sarojini Nagar Primary Healthcare Centre (PHC) in Lucknow district.

Somewhat similar has been the experience of Krishna Chaurasiya, another ASHA bahu in Banthra village. She had visited Deepak Gautam, a village resident, who had point blank refused to take the antifilarial drugs.

The direct to consumer digital awareness campaign by Uttar Pradesh government has aided the healthcare staff in administering the filariasis drugs better.

Surprisingly, the following day she found him at her doorstep asking for the medicine.

“What changed?” Krishna asked him.

The change of mind was thanks to an Interactive Voice Response call and a WhatsApp message Gautam had received, informing him that hathi paon medicines had to be consumed even if a person wasn’t infected. In Uttar Pradesh, filariasis disease is locally known as haathi paon (elephantiasis or elephant foot, as in filariasis the feet of the patients swell).

The credit for this transformation in the behaviour of rural masses goes to the Direct to Consumer Filariasis Awareness Campaign (D2C) of the Uttar Pradesh government. The campaign is in line with the launch of the Mass Drug Administration (MDA) programme, which was kickstarted by the Union Secretary for Health & Family Welfare, Rajesh Bhushan on February 10 this year, with an aim to eliminate the endemic disease by 2027, three years ahead of the global target.

The Mass Drug Administration programme was launched nationwide on February 10 by the Union Secretary for Health & Family Welfare.

“We ran the campaign, to reach out to ASHAs, general public, school principals via IVR calls and WhatsApp chat bots educating them about filariasis, and guiding them how to consume the drugs,” Shreya M, communications officer, Uttar Pradesh Technical Support Unit (UPTSU) of IHAT (India Health Action Trust), told Gaon Connection.

The Direct to Consumer Awareness Campaign was run by Uttar Pradesh Technical Support Unit (UPTSU) of IHAT (India Health Action Trust), to aid the National Health Mission of Department of Health and Family Welfare, tackle filariasis in 18 endemic districts, out of the 51 endemic districts in the state.

Banthra village with a population of 5,049 has four ASHAs and one Sangini, who were the grassroot health activists to run the Mass Drug Administration programme.

The technical unit is also seeking a single-click response on WhatsApp, to track who has consumed the medicines.

“The process is ongoing. Once we have the complete data, we will be preparing an analytical data dashboard to be accessed by the health ministry,” Shreya said.

A leading cause of disability

Lymphatic Filariasis (LF), elephantiasis or hathi paon, is estimated to be one of the leading causes of disability worldwide. It causes an abnormal swelling of limbs.

According to the National Vector Borne Disease Control Programme (NCVBDC), Uttar Pradesh recorded 83,106 Lymphoedema (chronic Lymphatic Filariasis) cases, accounting for 15 per cent of the total caseload of 525,440 in the country in 2021. This is the second-highest after Bihar.

Lymphatic Filariasis is incurable, and according to the World Health Organization, the elimination of the disease is only possible by stopping the spread of the infection through preventive medication. Irrespective of having the disease or not, people in endemic districts need to have the medicine, to safely clear microfilariae from the blood of infected people.

Under the MDA programme, the drugs are administered to people, free of cost, every year.

Banthra village falls under the administration of Sarojini Nagar Primary Healthcare Centre (PHC) in Lucknow district.

Sundari Tharu from Amberpur village said she couldn’t even recall when she contracted hathi paon. “My feet hurt if I walk and my sole feels like it’s on fire. I am always troubled by joodi-bukhar,” Sundari told Gaon Connection. The 58-year-old and her husband Jagroop, have spent a major chunk of their life savings on finding short term respite through injections to control her fever and pain. Even fetching water from a handpump, hardly fifteen steps away, is excruciating for her.

Sundari Tharu and her husband Jagroop from Amberpur village have spent most of their life savings in finding short term respite for Sundari’s hathi paon.

ASHAs are identifying filariasis patients in their villages. For instance, Sangini Neetu Rawat, who heads a cluster of eight ASHAs of the Banthra sub-centre, has identified 25 such cases. The Banthra sub-centre comprises eight villages including Amberpur and Banthra, with a cumulative population of 10,203.

WhatsApp, Radio and IVR calls

Gaya Prasad’s faithful companion, his radio, kept him informed about haathi paon. The 73-year-old who is visually-challenged was kept abreast about the disease and the importance of taking the medicines to combat it.

“My day starts by listening to the samachar on my radio. They had announced about haathi paon, so, when the ASHA bahu came to give us the goli, I took it readily,” Gaya Prasad who lives in Banthra, told Gaon Connection.

Similarly, when ASHA bahu Sadhna, visited 57-year-old Braj Bahadur Singh, living in Banthra bazaar, he made no protest and took the antifilarial drugs for the first time in his life. He too had received a WhatsApp message telling him to do so, he said.

This year, there is next to no reluctance or resistance to taking the medicines, Ritu Srivastava, the District Vector Borne Disease Officer told Gaon Connection.

Also Read: ‘Regulation of healthcare in rural India absolutely critical to achieve universal health coverage’

ASHAs have been given special training on administering antifilarial drugs. Savita is one of the four ASHA bahus, responsible for getting 1,280 of 5,049 Banthra village inhabitants to take the Albendazole, D.E.C. and Ivermectin tablets.

In a day-long training session held at the PHC of Sarojini Nagar, Savita was introduced to the newly added Ivermectin drug which was to be administered based on a person’s height (none for below 90 cm, a single tablet for 90 cm to 119 cm, two tablets 119 cm to 140 cm, three for 140 cm to 158 cm, and four for a person measuring more than 158 cm). A measuring tape too was handed over to her for this. The training was run from January 27 to February 2, for different batches of ASHAs.

Campaign mode on

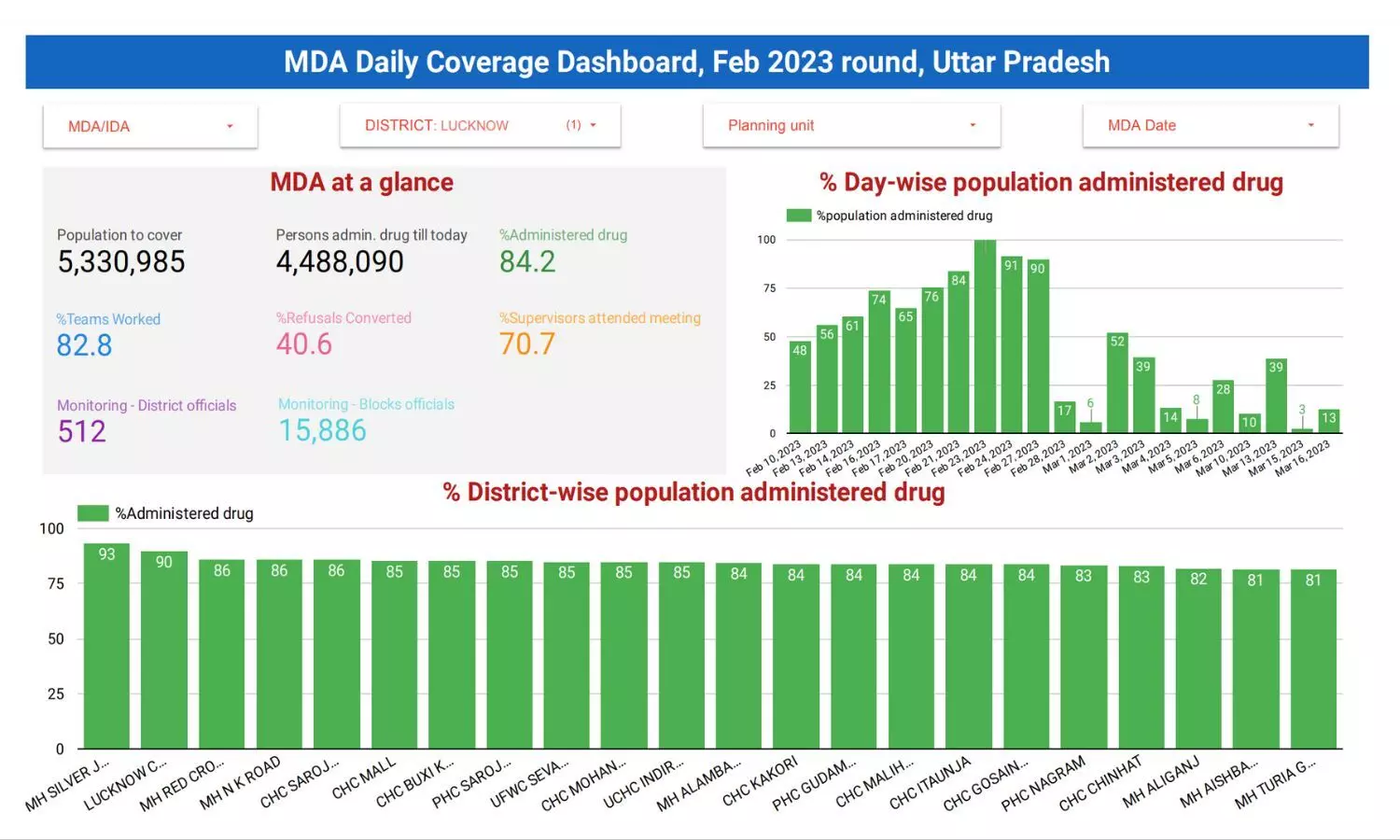

Based on a district-level Mass Drug Administration report, 84.2 per cent, that is 4,488,090 out of 5,330,985 target population in Lucknow district, were administered antifilarial drugs between February 10 and March 16.

The report also revealed that 40.6 per cent of drug intake refusals were converted in the district; and 70 per cent in blocks under the Sarojini Nagar PHC. The healthcare staff credits the digital awareness campaign contributing to these numbers.

Ram Janki Pal, Health Supervisor of Sarojini Nagar PHC, headed 75 teams during the MDA campaign of which nine were from Banthra.

“The campaign saw a good response from people this time. The ASHAs had lesser roadblocks,” she told Gaon Connection.

Kiran, a part of the Social Mobiliser Committee — a PHC level committee to mobilise the communities during the drug administration — apart from training the ASHAs, had also looped in self-help groups, kotedars, pradhan and school authorities to help.

The UPTSU is seeking a single click response on WhatsApp to know if a person has consumed anti-filarial drugs.(Left)

The data collected by the ASHAs is being uploaded on a digital portal E-Kavach.(Right)

“The mass media awareness drive gave us a ready pitch to build on. When we visited people, they had already received either a call or text about the filariasis control programme,” Kiran told Gaon Connection.

“We didn’t just distribute medicines this time but also administered them,” Ritu Srivastava, district officer for vector-borne disease, told Gaon Connection.

Rigorous Monitoring and Digital Data Recording

Savita was trained to draw a four-part divided square on the walls of each house she visited under the MDA programme.

“We had to write the house number, total family members, how many of them took the drug and the date of administering the drug. We also had to mark the index finger nail of the users, using permanent markers, to indicate the drug consumption,” Savita explained.

This practice helped mobilisers and supervisors like Kiran and Ram Janki monitor better and “reach out to families which had partial coverage”, Kiran said.

Now the last leg of the campaign for ASHAs remains: digital recording of filariasis MDA data.

E-Kavach is a digital portal which was launched in 2022 for recording immunisation and health data. It is being used to update filariasis data as well.

“The digital records have longer shelf life and are a great way to avoid the time lag of data movement from ASHAs to district health bodies,” said Ritu Srivastava.

The ASHAs are expected to record the MDA coverage against each family surveyed.

Uttar Pradesh is the state with the second highest filariasis burden in the country.

The ASHAs have already collected the data manually and now have to re-enter the same on e-kavach. The deadline for the same was March 31, and there was some anxiety about meeting the deadline as the internet has been erratic for several days in places. And while for some like Savita, it has been an easy to follow process, for others it has meant considerable effort.

Champa, the oldest amongst all the ASHAs of Banthra village, found the task exasperating. The 65-year-old depends on her grandchildren to help her with e-kavach data upload.

Ritu Srivastava, District Vector Borne Disease Officer.

But the much younger Savita said, “This is much easier. I just had to enter Ivermectin dosage. In the register, I have to write so much information.”

“E-kavach is still at a nascent stage and it would be hard to know the exact efficiency. Digital data will be useful in the long run but presently the challenges persist. We have received only 27 per cent of data through the portal as of now,” said Ritu Srivastava.