SONAL JAITLY

In recent times,

financial inclusion has received tremendous attention from policymakers as a

development objective. They see it as a prime facilitator for the efficient

delivery of social programmes like the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment

Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) or other Direct Benefit Transfer (DBT) enabled schemes.

As a result, achieving greater financial inclusion now tops the policy

priorities for inclusive growth in India.

And this focus

shows up in the numbers. The percentage of adults who have a bank account in

India increased to 80 per cent of the population in 2017, up from 53 per cent

in 2014. The Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojana (PMJDY), which was announced in

2014, helped open 36 crore bank accounts, with over 50 per cent of these

account holders being women. The gender gap in account ownership has also shrunk

from 20 per cent three years ago, to six per cent today.

However, a closer

look at these numbers reveals gaps, primarily around usage. While access may

have improved with supply-side efforts, demand-side efforts for financial

inclusion still attract little focus and investment in India. This is evident

in half of the new accounts being inactive, especially for women account

holders.1

One of the

primary barriers to active usage of formal financial services is the lack of

financial literacy. Women in rural areas have limited or no access to

information on how to engage with the continuously evolving formal financial

space, especially when it is online and digital. They also have limited

literacy levels, constrained mobility and access to public spaces, and are

intimidated by the male dominated physical banking space and the English

dominated online financial interfaces.

In a country

where 23.5 per cent of rural households have no literate adult above the age of

25 (one of the categories of deprivation measured by the Socio-Economic Caste

Census 2011), and of the 64 per cent literate rural Indians, more than a fifth

have not even completed primary school, it is not only important — but

essential — to have a systematic platform for financial education.

The inability to

understand and engage conveniently with the formal financial space has huge

implications on the financial behaviour of these households. This is further

exacerbated by language, connectivity, and socio-cultural barriers.

National level

efforts to enhance financial literacy have been focused on setting up of

Financial Literacy and Counselling Centres (FLCCs) by lead banks of a district.

FLCCs are meant to be the district level structures for imparting financial

education. However, they have not been very effective, especially given their

camp-based approach to financial education and limited outreach.

A gendered approach to financial education has a positive ripple effect on other key socio-economic indicators | Pic: SIDBI PSIG

A gendered approach to financial education has a positive ripple effect on other key socio-economic indicators | Pic: SIDBI PSIG

Financial

exclusion for women is different from that for men

To make sure

women benefit as much as possible from the programme, it is important to understand

why financial exclusion for women is different from financial exclusion for

men.

SIDBI’s PSIG

programme, supported by the Government of UK, offers key insights into how a

gendered approach to financial education and capacity building has a positive

ripple effect on household health, sanitation, education, and other key

socio-economic indicators.

The Financial

Literacy & Women Empowerment (FLWE) programme comprised pilot and scale-up

programmes on gender and financial capability building, and was implemented in

four states — Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, and Odisha.

The programme

focused on capacity building of rural women on gender issues, their rights and

entitlements, basic health, sanitation, and a detailed module on financial

well-being. It used a mix of classroom teaching, learning by doing,

audio-visuals, and technology-based interactive platforms for delivering

trainings. Each woman received an average of 30 hours of training over 15-18

months. The trainers were chosen from amongst the community and trainings were

followed by financial linkages, mass awareness camps, exposure visits to ATMs

and banks, which helped these women to link with financial products and

services of their choice.

The independent

endline evaluation of the programme revealed a number of benefits for women.

The trainings and exposure visits raised their confidence in dealing with

formal financial institutions, enabled them to play greater role in household

financial decision-making, and resulted in positive change in attitude of male

members who attended the trainings. In terms of numbers:

- Subscription to local ponzi schemes went down

from 32 percent to two percent. - The number of women contacting their local

microfinance institution staff for assistance rose from 41 per cent to 66 per cent,

as women began to understand grievance redressal mechanisms. - There was an improvement in awareness of

MNREGA benefits; it rose from 13 to 33 per cent. - Clients opting for insurance increased from 53

per cent to 85 per cent.

Key learnings

about building financial capability for low-income women across geographies and

languages

Having helped

build the financial capabilities of more than five lakh women in four states we

learnt a great deal about financial capability building for low-income women

across geographies, and in diverse languages.

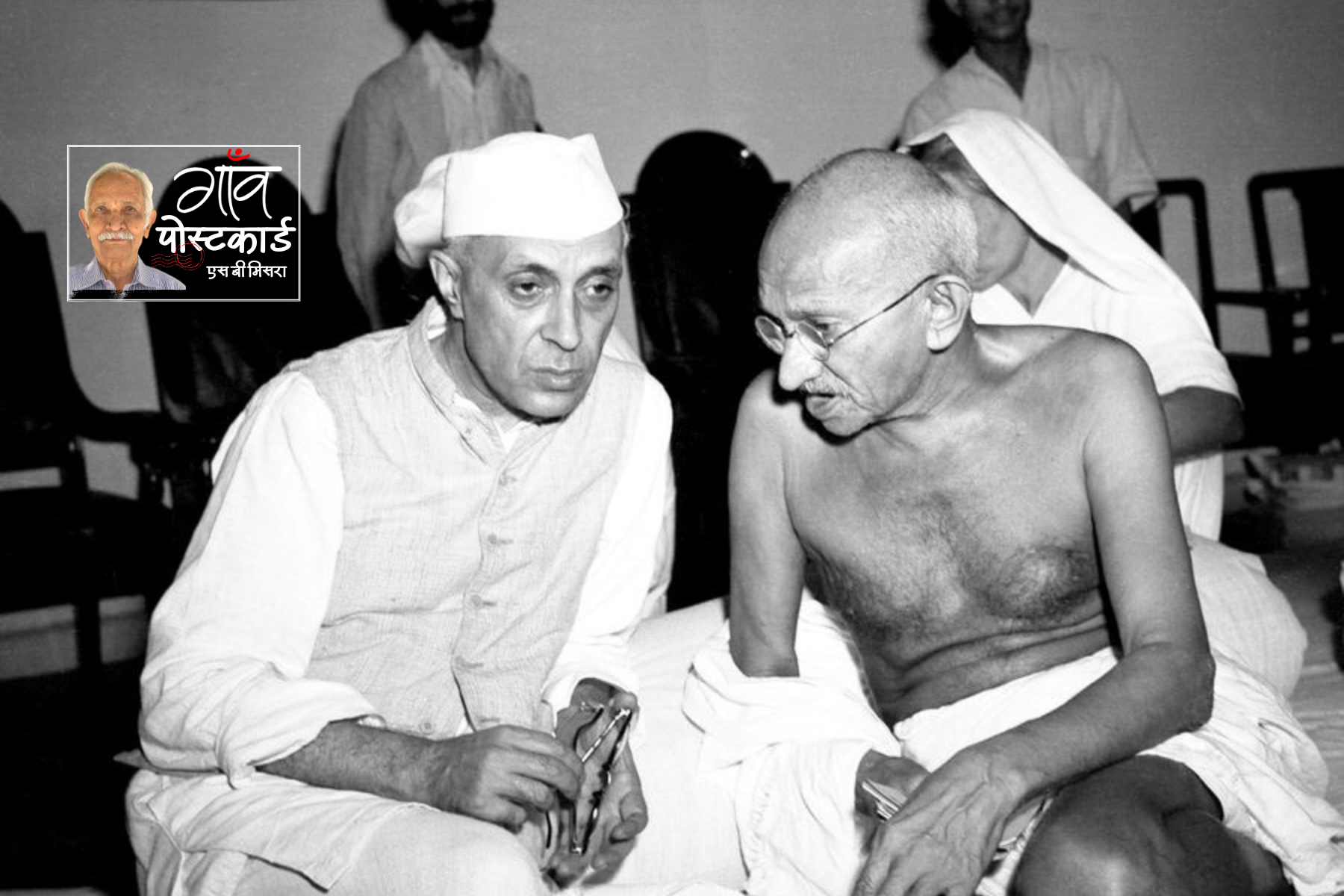

Women in rural areas have limited access to information on how to engage with the formal financial space, especially when it is online and digital. Pic: Gaon Connection

Women in rural areas have limited access to information on how to engage with the formal financial space, especially when it is online and digital. Pic: Gaon Connection

Programme

design

Financial

capability programmes have to be integrated with gender issues to effectively

address barriers to women’s financial inclusion. Gender integrated FLWE

programmes have strong returns, not only in terms of improved financial

behaviour, but also improved mobility and higher confidence.

Behaviourally-informed

content and visual aids using storytelling helps in better retention of

financial concepts by women.

Mobile IVR based

short episodes on FLWE are also effective in providing customised need-based

learning. However, it has to be complemented initially with on-ground

volunteers and frontline workers to create awareness and demonstrate usage of

such platforms.

FLWE programmes

generate increased demand for financial services. However, when women face

problem in accessing these services through local institutions, it demotivates

them and erodes their confidence. It is therefore important to bring all

stakeholders — like local bankers, government departments, and panchayat office

bearers — on one platform in the community. This can be effectively through

mass awareness camps where the local functionaries interact with the local

community about financial services and products.

Outcomes for

women

Women were able

to cope better during stress periods and financial emergencies, as the

programmes improved savings, provided the women an understanding of

entitlements under government schemes, and access to financial security

measures like insurance and pension.

Financial

capacity building followed by financial linkages leads to better understanding

about accessing relevant financial products from right institutions. It also

leads to significant reduction in vulnerability to financial frauds and ponzi

schemes.

There was a

significant change in women’s perception. Prior to the training, women

perceived financial products as a ‘luxury’, suitable only for the better-off

households.

Women with very

low levels of family income and very low levels of education benefitted

significantly from the trainings imparted. The evaluations confirm the highest

value of training for the most disadvantaged segment.

More

participation by men in trainings encourages joint decision-making at a household

level. However, given field realities and socio-cultural taboos, it is

difficult to ensure regular participation of men and women at the same time.

Women’s lack of

independent disposable income is the key barrier to increased usage of

financial products. The FLWE programmes witnessed an overwhelming demand from

women for skill development and income generating activities. Our research

corroborated that active account usage, and usage of financial products

increases if women are gainfully employed.

There is an

urgent need for greater investment on the demand side of financial inclusion

using gender integrated approaches to financial capability building, so we can

extend the gains of more women having bank accounts, to more women meaningfully

using important financial services like insurance, credit, and the next

frontier of cashless and mobile financial services.

Footnotes

54 per cent of

women account holders reported not using their account, as opposed to 43 per cent

male accountholders.

(Sonal Jaitly is

Theme Leader, Gender and Financial Literacy, at the Small Industries

Development Bank of India’s (SIDBI) Poorest States Inclusive Growth (PSIG)

programme)

This article was

originally published on India Development Review and can be viewed here.